The Conquest

Things went along swimmingly for the Incas for a few generations until the current Inca and the heir apparent died in a plague that swept through the empire (probably European Smallpox that had been introduced in North America and worked its way South). With no clear leader, the empire dissolved into a civil war that drained the resources and energies of the empire until the northern faction, under the Inca Atawallpa, emerged victorious. It was at this time that Francisco Pizzaro and his decisively un-merry band of unlettered soldiers and mercenaries showed up on the scene. The timing was propitious for Pizarro and his men. He found exactly what he had been looking for: a culture rich in gold and silver that was ripe for exploitation. Pizarro landed near the city of Cajamarca in 1533 as Atawallpa, the Inca who had recently emerged victorious from a devastating civil war, happened to be passing through the area on his way back to Cusco. Atawallpa was curious about the strangers so he invited them to visit his court. He was not worried about any threat presented by the Spaniards as he had several tens of thousands of troops with him and Pizarro was accompanied by only 40 cavalry and 150 foot soldiers. However, Pizarro saw his opportunity and, in a devious but brilliant military maneuver, had his men lay in wait while he asked for a peaceful audience with the Inca under a pledge of truce. When Atawallpa arrived with his retinue, Pizarro´s troops lept out of hiding and captured the Inca. Without direction from their leader, the Incas were left in a state of confusion while the Spaniards pressed their advantage. Even though Pizarro´s men were dreadfully outnumbered, the stone weapons and slingshots of the Incas proved no match for the Spaniards on horseback who slaughtered literally thousands of Inca troops without a single Spanish loss. Atawallpa promised a ransom of a storehouse filled once with gold and twice more with silver if he were released. The Spanish eagerly agreed but once the ransom was paid, they decided that Atawallpa would be too dangerous if released so they killed him.

Other than the virulent germs carried by the Spanish, the most decisive weapon of the conquest was the horse, the tank of the Conquest. One mounted Spaniard was virtually untouchable by attackers on foot while he could kill them almost at will. While the Spanish had muskets, guns would not become a major factor until the invention of the repeating rifle. Time and time again, the Spanish cavalry would win battles in which they were almost always outnumbered. The hierarchically-structured administrative system that was so central to the Inca’s success was now a key component to their defeat and subjugation. Without their leader at the top of the chain of command, the Incas found it difficult to organize a concerted defense or counter-attack and, once in control, the Spanish simply inserted their rulers into the existing top of the chain of command.

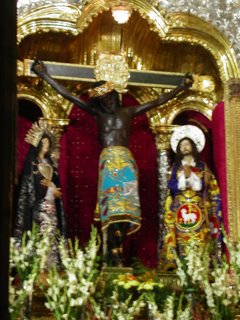

The first Spanish on the scene in Cusco were solely concerned with looting and pillaging. Any precious metals that could be grabbed were melted down and carted away; all of the treasures of the Qoricancha ended up in the crucible. But, then, two years later, Pizarro´s puppet Inca, Manco II, escaped and returned with an army of between 100,000 and 200,000 and captured the fortress of Sacsaywaman, laying a six-month siege to the city of Cusco below. All was almost lost for the Spanish until they engaged in a last-ditch flanking maneuver and were able to recapture Sacsaywaman. Manco II retreated to his mountain hideout of Vilcabamba where he was succeeded in his rebellion by Inca Tupac Amaru but, for all intents and purposes, the uprising was over. In 1780, Tupac Amaru II led another surprise rebellion that shocked the Spanish throne. He came close to succeeding but was eventually captured and returned to the main square of Cusco where he was put to death, but only after he was forced to watch his family be killed first.

Once in power, the Spanish destroyed the cooperative Ayllu system in favor of the encomienda system where large pieces of land were granted to Spanish encomienderos who, ignoring knowledge gained by the Incas, introduced European grazing and agricultural practices with disastrous results. The European grazing animals destroyed fragile Andean topsoil and the planting of cash crops such as coffee both eliminated the natives ability to grow food for themselves and destroyed the land in the process by not rotating crops or allowing land to lay fallow. The natives themselves were literally worked to death by the encomienderos whose responsibility to the natives ended with the teaching of Christianity.

Interestingly, it wasn’t the debt-ridden Spanish Crown that primarily benefited from the colonization of the new world but the bankers of England and Northern Europe. The colonization of the new world was also the turning point for the ascendancy of Europe at large as the pre-eminent world power. Prior to 1492, Europe was a global backwater. It was just coming out of the Dark Ages and had been enfeebled by the Black Death that had killed one out of every three people. Sewage flowed freely through the streets of large cities, the dead were unceremoniously dumped in large “dead holes,” and many women were forced to turn to prostitution. In comparison, the new world seemed idyllic to many of the early explorers. In terms of global power, Europe was insignificant compared to the Moslem empire which stretched from Northern Africa all the way around the known world to Indonesia or to the powerful Asian empires of China, Japan, and India. However, in just a few short years, the ranks of Christians in the world swelled from a few million Europeans to the largest religion in the world and the raw materials and cheap labor of the Americas fueled both European industrialization and continued colonial imperialism throughout the globe.

Even with independence the situation of European domination of the indigenous peoples of the Americas has changed but little. Except for a small percentage of white-skinned Peruvians of primarily European descent, the rest of the population are either full-blooded or nearly full-blooded Indians or mestizos whose familial lineage includes some mix of Indian and European blood. Although most people consider themselves to be “mestizo,” this is not to say that the color of one’s skin is not without consequence. The reigns of political and economic power are still primarily held by those with primarily white faces while those of darker complexion find themselves at the bottom of the economic ladder. Even among the poor there is a demarcation based on skin color. We were recently eating dinner with some friends and Zak´s thirteen-year-old friend reminded Zak and I to take off our hats before we eat because "only Incas wear hats when they eat." When I asked what he meant he said that the campesino indians always wear their hats when they eat implying that (light-skinned) social graces prohibited such behavior.

As Cusco is the second largest city in Peru, I had the opportunity to see many election rallies prior to the recent elections and I was shocked to see that the faces of most candidates were much more similar to my own than to the voters whose favor they hoped to curry. The entourage of most of the candidates actually included a group of dark-skinned mestizos or indians in indigenous dress to stress the candidate’s sensitivity to the needs of the “common” man in a way that did not threaten the power elite of primarily European descent.

In Peru, most of the Indians or darker-skinned mestizos speak Quechua or other indigenous languages; they generally live in the countryside (the campo) and are thus referred to as campesinos (literally peasants). Some have moved to the cities in order to find an education for their children or in hopes of finding better economic opportunities. Indicative of this group is my friend Jaime. He has a taxi and I have hired him a number of times to take us on daily excusions to areas of interest around the city. Most tourists simply hire bus tours but I usually have some other out of the way place I want to go in addition to the major tourist stops and I like the flexibility of being able to set my own itinerary. Jaime grew up in the altiplano, the highland campo to the Southeast of Cusco. Much of this area is above the tree line and, as it gets quite cold, houses are small and often adjoin the livestock stables to conserve warmth. The primary fuel for cooking and heating is dried llama and sheep (what’s brown and sounds like a bell?) dung. Jaime was one of eight children (what else is there to do when it gets cold and you don’t have a television?). When his oldest sister was born, his mother did not produce any milk, possibly from malnutrition, so the baby was given away to an orphanage run by nuns and no one knows what has become of her or even if she is dead or alive. When Jaime was young, there was not enough food to go around, particularly in the months before harvest (February, March, and April). Although it sounds almost too stereotypical to be true, a friend who is a graduate student in Anthropology and has done field work in the campos, has found that alcoholism is rampant among adult males and that it is often the mothers who end up doing most of the work and feeding the family. This was true of Jaime’s family as well. As there were too many mouths to feed at home, Jaime left when he was ten years old and went to Cusco where he hoped to find work. He did work, very hard, and eventually reached the point where he was able to buy a used Toyota corolla and start a taxi service. His girlfriend is now pregnant and he seems very happy with his life (it is quite common to start a family after a period of courtship and only get married some years down the line if at all). His parents died in their mid 40s as a result of alcohol abuse and just harsh living.

As most of the countries in South America, including Peru, are considered to be fairly strong democracies, you may wonder why the impoverished majority don’t simply elect one of their own to lead the country and respond to their very dramatic needs? The answer lies in both the historic underpinnings of power (both religious and economic) in South America and in the very real threat of violence both from the domestic powers that be and from external forces such as the United States. Much has it has done since the conquest, violence still underpins power in much of the Americas, elections or not. For its part, the U.S. has been voicing extremely threatening rhetoric toward the recently-elected presidents of Venezuela, Brazil, Bolivia, and one of the two candidates (Ollantay) who will be running in the Peruvian run-off election next month. All of these officials received wide-popular support and are, consequently, viewed by Washington as threatening to the minority of the economic elite who grow richer as foreign economic imperialists, including those from the U.S., extract wealth from South America. Such an attitude is entirely understandable as long as one refrains from any consideration of justice or fairness, after all, how dare the people of South America believe that their resources belong to themselves? For example, in my travels, I’ve noticed that it isn’t easy to find a good cup in Costa Rica, Peru, or Bolivia even though these countries grow some of the best coffee in the world. The reason for this is that most of this coffee is grown for export. Most of the wealth generated by the raw materials exported from the Americas – oil, coffee, sugar, even cocaine – is not seen by the locals but by the exporters, processors, distributors, and retailers, all mainly foreigners. For the locals in Peru and elsewhere in South America, the recently signed free trade agreement is simple an agreement to pay for the continued acquisition of wealth by others.